Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

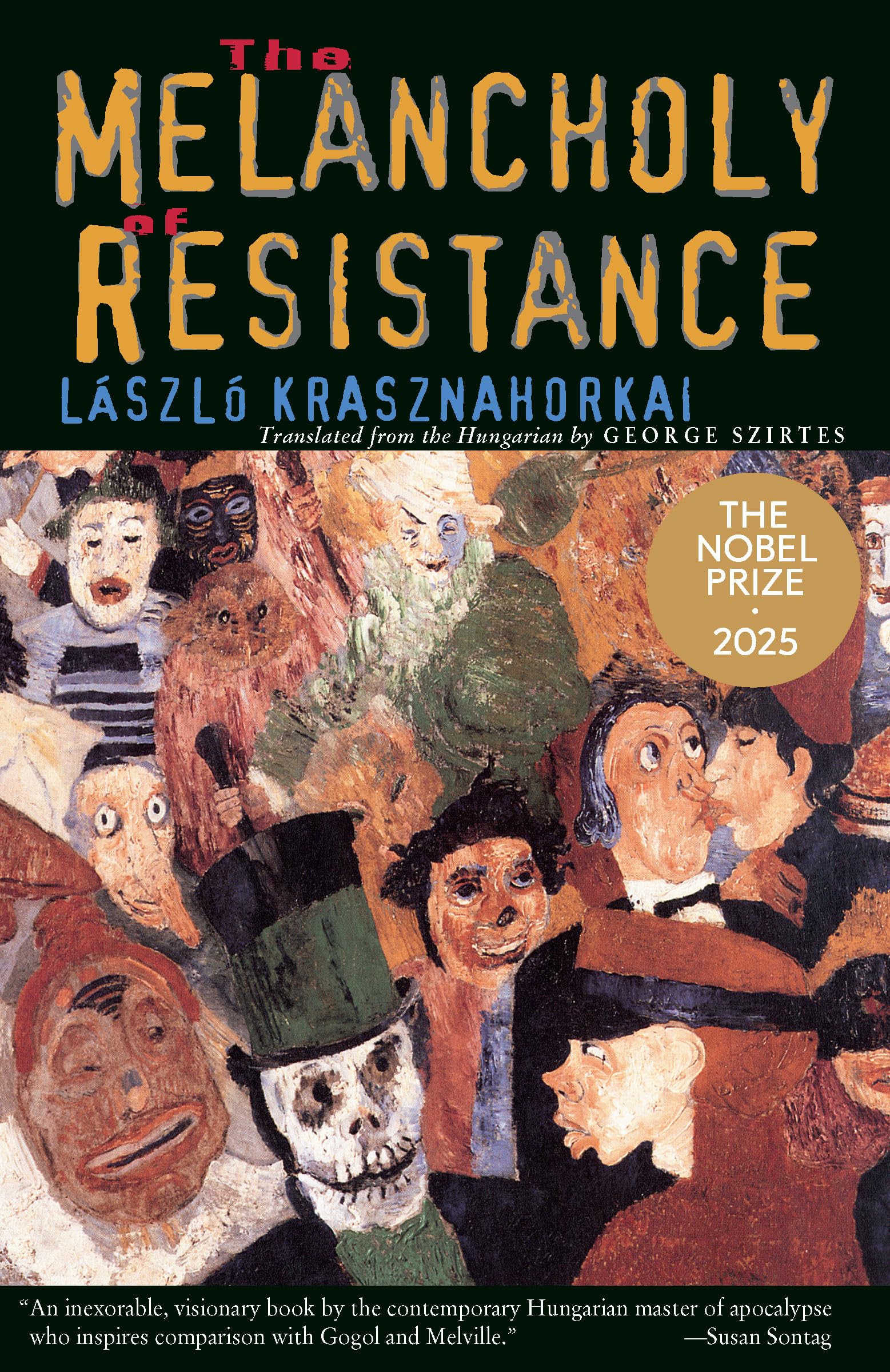

Buy New Directions The Melancholy of Resistance by Krasznahorkai, László online on desertcart.ae at best prices. ✓ Fast and free shipping ✓ free returns ✓ cash on delivery available on eligible purchase. Review: Amazing - Amazing read!!! Review: arrived damaged, but an excellent book

| Best Sellers Rank | #59,233 in Books ( See Top 100 in Books ) #1,026 in Contemporary Literature & Fiction #3,113 in Genre Fiction #4,031 in Literary Fiction |

| Customer reviews | 4.5 4.5 out of 5 stars (164) |

| Dimensions | 13.21 x 2.03 x 20.32 cm |

| ISBN-10 | 0811215040 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0811215046 |

| Item weight | 1.05 Kilograms |

| Language | English |

| Print length | 320 pages |

| Publication date | 17 June 2002 |

| Publisher | New Directions Publishing Corporation |

I**N

Amazing

Amazing read!!!

M**.

arrived damaged, but an excellent book

F**F

Gorgeous edition, I didn't like the second half of the novel though. It gets increasingly boring and eventually messed up.

K**R

Brilliant.

A**R

What a read !!!! Mind blowing writing the prose will make your head spin a style all his own !

I**N

The Nobel Prize jury called seventy-one-year-old Hungarian author, born in 1954, László Krasznahorkai, “a great epic writer in the central European tradition that extends through Kafka to Thomas Bernhard, and is characterized by absurdism and grotesque excess.” His family hid his Jewish roots from him until he turned 11. In 1931, when antisemitism was rampant in Hungary and Jewish lives were threatened, Krasznahorkai’s grandfather changed their family name from the Jewish-sounding name Korin to the now Hungarian-sounding one. Krasznahorkai used the name Korin for the Hungarian archivist protagonist in his 1999 novel “War and War.” In 2018, he said, “I am half Jewish, but if things carry on in Hungary as they seem likely to do, I’ll soon be entirely Jewish.” His mother was not Jewish. His novel The Melancholy of Resistance is a marvelous, strange, and unique literary experience. It is oppressive and transcendent, cryptic and profound. It was first published in 1989 and translated expertly into English by George Szirtes in 2002. It is an entry into the Hungarian master’s unsettling and hallucinatory world. James Wood wrote in the New Yorker in 2011: "The Melancholy of Resistance is a comedy of apocalypse, a book about a God that not only failed but didn't even turn up for the exam.” The novel is set in a decaying provincial Hungarian town gripped by winter, strange events, and inertia. The plot opens with a fascinating story of an aged woman seated on a train who is stared at by an unshaven drunk. She is convinced that the man wants to rape her. The man, in turn, believes she is trying to seduce him. The story continues for 33 pages—a tale that could stand and be enjoyed alone. But it is followed by a revelation that she is the mother of a young man who is mentally challenged—and we soon learn that his mom dislikes him, although he is the only good person in their bizarre town. Soon, the ominous arrival of a traveling circus brings a massive, grotesque stuffed whale. The whale disturbs the townspeople. It fills them with a creeping dread that the circus people have a deep and sinister plot in motion. There are mysterious power outages in the town, infrastructure collapses, and further anarchy that set the tone for a work that explores the fragility of order, the seduction of chaos, and the terrifying, destructive pull of authoritarian control. Three unforgettable characters capture our attention: Valuska, the aged lady’s son, whose innocent and comical view of the world makes him ridiculous yet very sympathetic. Mr. Eszter is a music theorist obsessed with pure tuning systems and longing for harmony in a world that refuses to offer it. He is a weakling, lazy husband who lives like a hermit. Mrs. Eszter, his estranged and ruthless wife, is determined to seize power and snatch control of the town by manipulating fear and disorder. She was a woman whose lover was the chief of police, and whom everyone in the city, including her husband, kept at arm’s length. The fates of these three intersect with The Prince, a mute, misshapen figure traveling with the circus, who may be a charismatic revolutionary or merely a figment of mass hysteria. This ambiguity is central to Krasznahorkai’s writing style: no clear answers, only uncertainty, prompting readers to wonder and think. This kind of ambiguity is not unique to Krasznahorkai. Other writers used it as well. In his 2025 introduction to Daphne du Maurier’s book “After Midnight, Stephen King calls her thirteen tales in the book “diabolical” because the British author (1907-1989) messes with her readers’ thinking when she fails to clarify whether the threats faced by her characters are external and real or only in their minds. The novel is therefore a challenge and a marvel. This and Krasznahorkai’s usual long, unbroken sentences sometimes seem like hurricane winds of thought, carrying readers through fever dreams, fogs of paranoia, melancholy, and revelation. Yet, his novel deserved the Nobel Prize. His novels reward readers with moments of mind-opening clarity and lyrical beauty. This novel, for example, begins with a sentence that spans half a page. It follows with its second sentence, like burning lava cascading downward to five lines before the end of the page. The writing style of long sentences and the absence of paragraphs appear on every page. Yet it may surprise readers that there is no difficulty in understanding —none at all —and they can thoroughly enjoy what is said. The novel is a very perceptive metaphysical and political parable. It captures how societies teeter on the edge of collapse not through violent revolutions, but through quiet failures, unchecked fears, and the slow corrosion of meaning. While showing the absurdity of existence, it is also consoling. We can snatch meaning from hands grasping despair. We can recognize humanity’s shared confusion and our resistance to meaninglessness. We can recall the message of the biblical book Ezra and Nehemiah that people can find bright silver linings even in dark thunder clouds, and the experiences of Viktor Frankl in Nazi concentration camps, where finding meaning saved his life.

Trustpilot

5 days ago

1 week ago