Customer Services

Customer Support

Desert Online General Trading LLC

Warehouse # 7, 4th Street, Umm Ramool, Dubai, 30183, Dubai

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

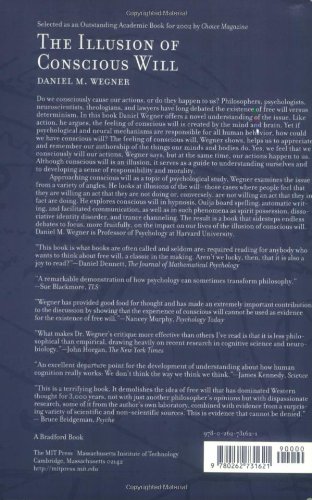

Full description not available

J**R

Good, but fails near the end

I loved the way this book started. For example, the evidence that people can feel they are controlling other people's actions is fascinating. The overall theory of how we feel we are willing things is well presented, as is the idea that such a feeling is an illusion. This isn't shocking stuff to some, but to others it will be a huge revelation.I do have complaints. For the tiny ones first (big one at the end). First, I object to calling the loss of pain and loss of memory during hypnosis examples of increased mental control. By that definition, Alzheimers patients have increased control. What one isn't aware of one isn't aware of and this hardly seems like control.As far as not being able to avoid thinking of things, it seems to me the explanation is simpler. Words conjure images, but negative words have no images associated with them so when you say "Don't think about a bear" the only word causing an image is bear, and so you think of a bear. Trying to monitor bear thoughts will lead to bear thoughts. Also he says, if you are distracted while you are trying not to do something you will be more likely to do it. I can see that since trying not to do something (like drop a jar) requires action in an opposite direction, i.e. it requires effort. But is this true when you are trying NOT to think of something? If I tried not to think of Wegner's white bear and was then asked to recite the Gettysburg address I strongly suspect I would forget the bear. Not thinking about something, unlike not doing does not require any positive action. Distraction ought to make it easier to forget and he never distinguishes between these and acts as if what is true of behavior is true of thoughts.But my BIG complaint is the last chapter. He suddenly claims his own theories only explain why we feel will, but he tried to minimize the impact of all this on morality and even started talking about will as a causal force again. He even seemed at times when using the word will to indicate something that wasn't necessarily conscious. This is nonsense. If will isn't conscious it isn't will.Our thoughts have causal impact on our actions, but then what is the cause of our thoughts? Clearly we don't control these either. They are a sum of what we are, what we have experienced, the way our brains are wired together etc. As far as morality I have to believe that the only thing we can judge is individual bits of behavior. Behavior is moral or not, acceptable or not and some people have a higher propensity to engage in unacceptable behaviors than others--whatever the reasons. As a society we have to judge behavior and engage in activities to modify the behavior of others when it is unacceptable and that is what our jutsice system should attempt. If an individual's behavior remains unacceptable or cannot be modified, we have an obligation to put them where they cannot engage in the behavior.Wegner is clearly unwilling to give up on the idea that people will their behavior and are thus responbsible in the traditional way for what they do. The idea that we can use "mens rea" a guilty mind to show a person willed their actions seems like a dubious standard to me. A person may not will their behavior but later feels guilty because they realize their behavior is in violation of their own moral code. A person totally lacking a developed moral code (a sociopath, let's say) would never exhibit a guilty mind. Are such folks les guilty? Or less dangerous?The whole issue of whether mental states should be considered in a legal system should be abandoned as far as I can see. I believe we should judge behavior and then decide what to do with the person engaging in the behavior. What we do should be motivated by our desire to 1) modify the person's behavior and 2) protect innocents. The strategy for each individual will vary depending on their mental abilities and their behavioral history etc and we may often get it wrong.Wegner's thesis has much bigger implications for our ideas about personal responsibility than he wants to admit and ultimately he is unwilling to really stick with his guns. That was a dissappointment.But the book has a lot of great stuff to say and I would definitely recommend it to anyone interested in mind/body questions.

T**S

Begs the more interesting question

Wegner makes the case for the idea that our conscious mind is the interpreter rather than the author of our actions, that our sense that our conscious mind is "in charge" is illusory, and that what we perceive to be our motivation for action is at best an educated guess by a neural system that has little or no access to those motivations. His argument boils down to generalizing a couple of well established facts: 1) there are detectable electrical events in the brain that precede our awareness that we have made a decision, implying that awareness of the decision follows rather than motivates the decision. 2) there are many circumstances in which we may take action without being conscious of making a decision to do so, and likewise situations in which we may feel that an action is the result of a decision when in fact we have done nothing. So far, so good. It is likely that our experience of consciousness simply requires too much computation, too many synaptic delays, for it to be fast enough to control our actions reliably in a world in which promptness is often at a premium.But it seems to me that Wegner begs the more interesting question of what influence, if any, our conscious mind has over our actions. If we accept that our conscious decisions are not the proximate cause of our actions, what influence does the conscious mind have over our behavior? After all, I can program a computer to take an action at a later time, without my direct intervention. So it is possible that while our conscious mind's experience of being the immediate author of our actions is illusory, it remains possible that our conscious mind is more indirectly in control--in essence, programming our unconscious mind. Wegner speaks of the importance of having a mental plan in creating one's sense of authorship over one's actions, but he does not address the possibility that that plan may influence those actions.

A**L

The free will paradox in the light of experiment.

Debates about free will have traditionally been a matter for philosophers, but advances in experimental psychology and neurophysiology now mean that science is altering the terms of the argument. Wegner draws on this information to put forward the view encapsulated by his title: namely, that the feeling of willing is an illusion.The first thing to say about this book is that it is refreshingly free from jargon. Wegner writes well and clearly and there are numerous witty asides. As an added bonus there are genuine footnotes at the bottom of the page instead of the usual tiresome end notes; congratulations to MIT Press for these.Research in the 1960s showed that there are measurable electrical changes in the brain in the run-up to a voluntary movement such as lifting a finger. Some regarded this as evidence for the input of a conscious self. However, later work by Benjamin Libet produced the disconcerting information that electrical brain activity begins before the person is conscious of the decision to move. The obvious implication is that consciousness appears to be an epiphenomenon or accompaniment to action rather than its originator.The essence of the view that Wegner wants to defend is encapsulated in a diagram on p.68. This shows both conscious thought and action as arising from unknown events in the brain. There are two pathways leading to action: the "real" but unconscious pathway that produces the action, and a second "apparent" pathway that produces the illusion of conscious initiation of action.This counterintuitive view is explained in the first few chapters, and the remainder of the book expands the idea with reference to various unusual psychological states such as automatic writing, mediumship and channelling, and hypnosis. Wegner shows that it is possible to think one is willing an action when one is not and also to will an action when one thinks one isn't. These strange situations come about because conscious will is, in fact, an illusion, and hence the brain can be tricked into thinking that will is present when it isn't or vice versa.If Wegner is right— and he certainly makes a very persuasive case for his view— the implications are clearly pretty disturbing. What are we to make of our ordinary ideas of responsibility, justice, retribution and so on? And why does this illusion of conscious will exist anyway? The philosophical aspectes of the theory are treated, albeit rather briefly, in the final chapter.Wegner compares the conscious will to a ship's compass. The compass does not directly control the movement of the ship but it is nevertheless essential for navigation. This is an interesting metaphor, but of course one could say that the compass is linked indirectly to the steering via the brain of the helmsman. However, Wegner's argument, as I understand it, is that there is no necessary connection between the compass reading and the movement of the ship. I suppose one could contrast the compass with the automatic pilot of an aircraft, which does control how the plane flies.Free will, Wegner suggests, is best thought of as an emotion. "The experience of will marks our actions for us. It helps us to know the difference between a light we have turned on at the switch and a light that has flickered on without our influence… Will is a kind of authorship emotion." The feeling of willing, it seems, is an illusion but a necessary one.Many philosophers have reached the same conclusion as Wegner does in this book. The difference is that they support their arguments with abstract reasoning whereas Wegner does so with direct experimental evidence.

D**A

A BOOK WORTH READING

Summary: The experience of conscious will is not a direct indicator of a causal relation between thought and behavior.It has been a while since I found a book so interesting that I felt compelled to write an opinion for others prospective readers. Well, for a start much of the pages require your full attention, at least in some sections, which is already a good thing. The best is that the author is so much competent and at ease with the subject that he does not use vague difficult sentences to explain the matter, but the most simple vocabulary. That said, once in a while he seems to forget about his not so expert readers and just start writing for his colleagues only.This is especially important for me, since English is not my mother tongue, neither a language I regularly use. By the way, in my opinion it is time that American writers stop assuming that all theirs readers are Americans grown up in the States and when they wish to pick up an example choose something from their own culture only (Easter’s bunny, peanut butter and jelly sandwich, football, Tooth Fairy).In Chapter 4 I had been intrigued but the “ the perversity of automatisms” and also relieved to read how common this event does happen in human beings. With the occasion, I was surprised not to find “playing the piano” (it happened to me) and may be other musical instruments in the same company of automatic writing, pendulum et Co.. In Chapter 6th action projection is readily understood thank you for the example of Pinocchio as a puppet became alive when a person operates as a Geppetto. Finally an example taken from the Italian Carlo Collodi.I believe most of readers will find something of special interest for them in this book and they are not going to waste their time and money.

N**.

Außergewöhnlich lesenswerte empirische Untersuchung der Willensfreiheit

Verursachen wir bewusst unsere Handlungen oder passieren sie uns? Philosophen, Psychologen, Neurologen, Theologen und Rechtswissenschaftler haben lange über die Existenz des freien Willens im Gegensatz zum Determinismus diskutiert. Professor Daniel M. Wegner der Universität Harvard bietet in diesem Buch ein neuartiges Verständnis dieser Frage. Wie Handlungen auch, so argumentiert er, wird das Gefühl bewussten Willens durch Geist und Gehirn erzeugt. Wenn aber psychische und neurale Mechanismen für alles menschliche Verhalten verantwortlich sind, wie können wir dann bewussten Willen haben? Daniel M. Wegner zeigt, dass uns das Gefühl bewussten Willens hilft, unsere Urheberschaft bei Dingen zu erkennen, die unser Geist und unser Körper tun, und diese Urheberschaft zu erinnern. Wir fühlen, dass wir unsere Handlungen bewusst wollen, uns aber unsere Handlungen gleichzeitig passieren. Auch wenn bewusster Wille eine Illusion ist, dient er als ein Anhaltspunkt dafür, uns selbst zu verstehen und ein Gefühl von Verantwortung und Moral zu entwickeln.Daniel M. Wegner nähert sich bewusstem Willen als Gegenstand psychologischer Untersuchung und betrachtet die Frage von Vielfältigen Blickwinkeln. Er untersucht die Illusion des Willens anhand von Fällen, bei denen Menschen fühlen, dass sie eine Handlung wollen, die sie tatsächlich nicht tun, oder umgekehrt, dass sie eine Handlung nicht wollen, die sie tatsächlich tun. Er erforscht bewussten Willen bei der Hypnose, bei Oui-ja-boards, bei automatischem Schreiben und bei gestützter Kommunikation (facilitated communication), wie auch bei Phänomenen wie Besessenheit, dissoziativen Persönlichkeitsstörungen und Channeling. Das Buch "The Illusion of Conscious Will" weicht endlosen Debatten aus, um die Wirkungen der Illusion des bewussten Willens auf unser Leben in den Fokus zu stellen."The Illusion of Conscious Will" ist ein außergewöhnlich lesenwertes Fachbuch für all diejenigen, die sich mit dem Phänomen der Willensfreiheit und der Funktionsweise des menschlichen Gehirns beschäftigen. Ebenso werden zahlreiche spirituelle Phänomene entmystifiziert. Anhand exzellenter empirischer Analysen zeigt Daniel M. Wegner, warum es sich bei der Willensfreiheit um eine sehr nützliche Illusion handelt. Gleichzeitig zeigt er, warum die Erfahrung bewussten Willens nicht als Beweis für die Existenz des freien Willens herangezogen werden kann. Als empirisches und weniger philosophisches Werk bietet es eine hervorragende wissenschaftliche Grundlage für die weitere Diskussion klassischer philosophische Fragestellungen, sodass gerade auch Philosophen diesem Werk große Beachtung schenken sollten.

J**K

Great book

Very interesting book on the topic of conscious will. Detailed, informative, often humorous. Similar to anatta of Buddhism.

L**N

A must read if you are interested in neuroscience

This book takes you to the nuts and bolts of neuroscience.

Trustpilot

2 months ago

4 days ago