Customer Services

Customer Support

Desert Online General Trading LLC

Warehouse # 7, 4th Street, Umm Ramool, Dubai, 30183, Dubai

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

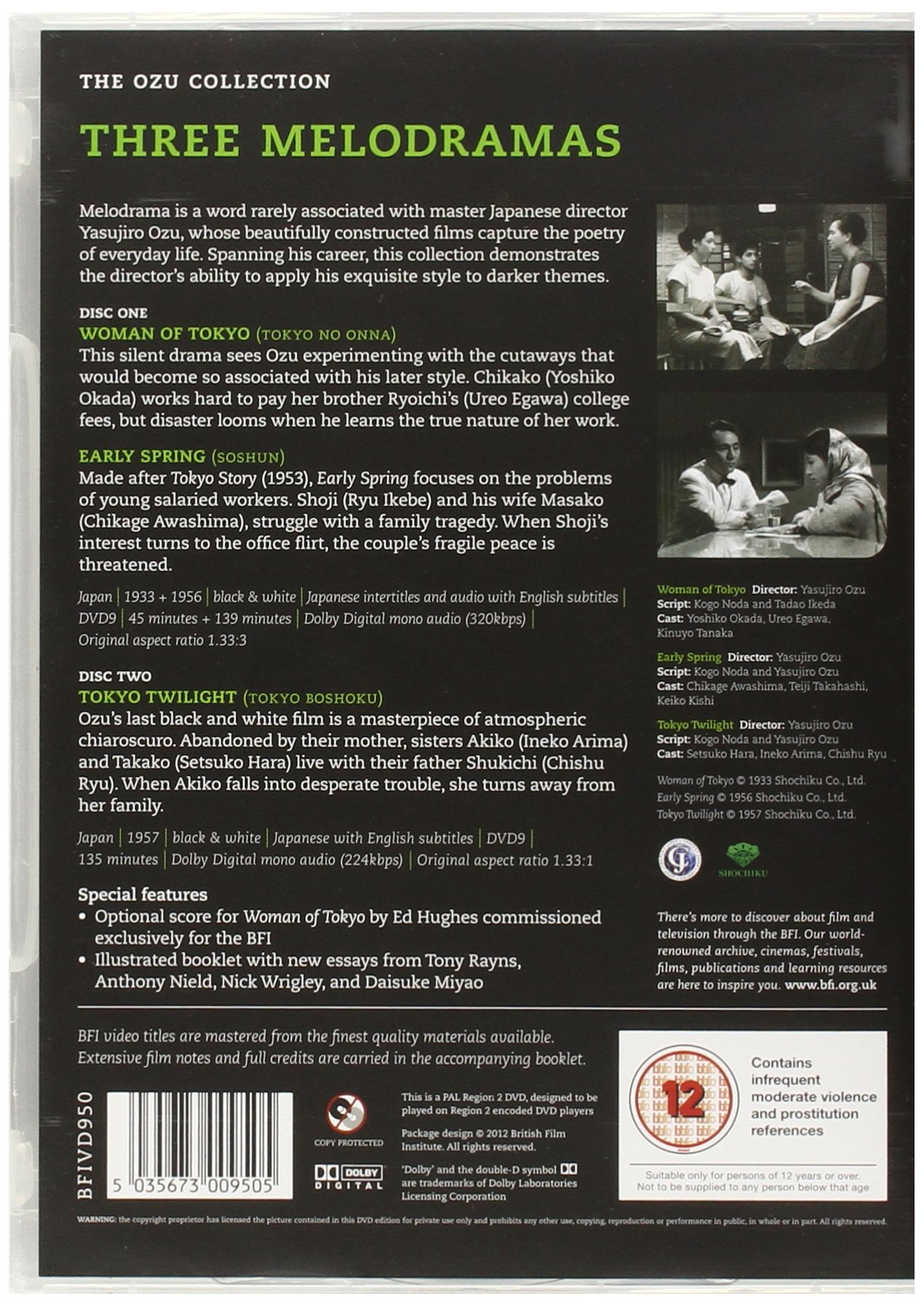

![Ozu - Three Melodramas (2 DVD set) [1933 - 1957]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71VroGLw5pL.jpg)

Ozu - Three Melodramas (2 DVD set) [1933 - 1957]

Trustpilot

2 weeks ago

1 month ago

2 weeks ago

1 month ago