Customer Services

Customer Support

Desert Online General Trading LLC

Warehouse # 7, 4th Street, Umm Ramool, Dubai, 30183, Dubai

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

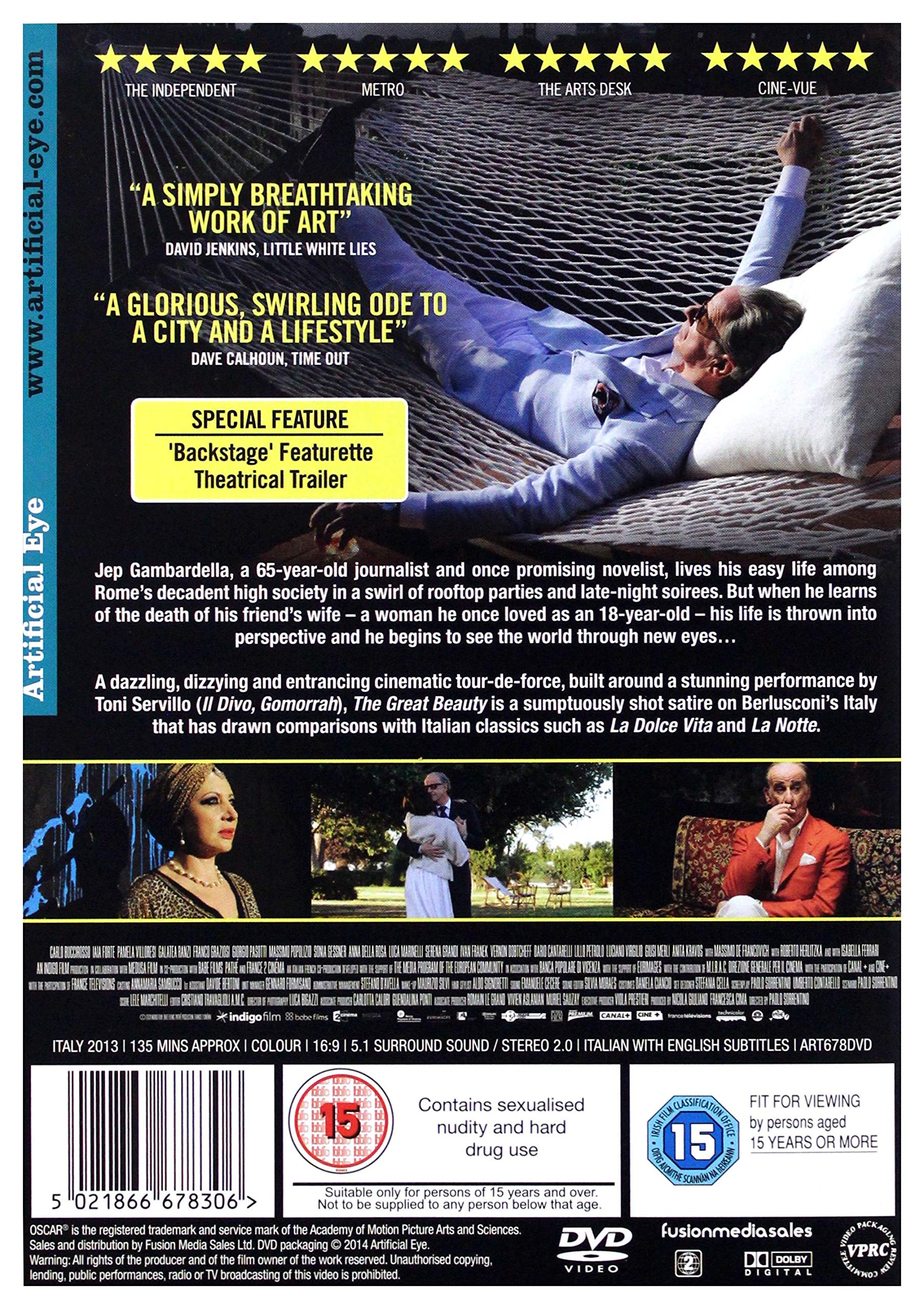

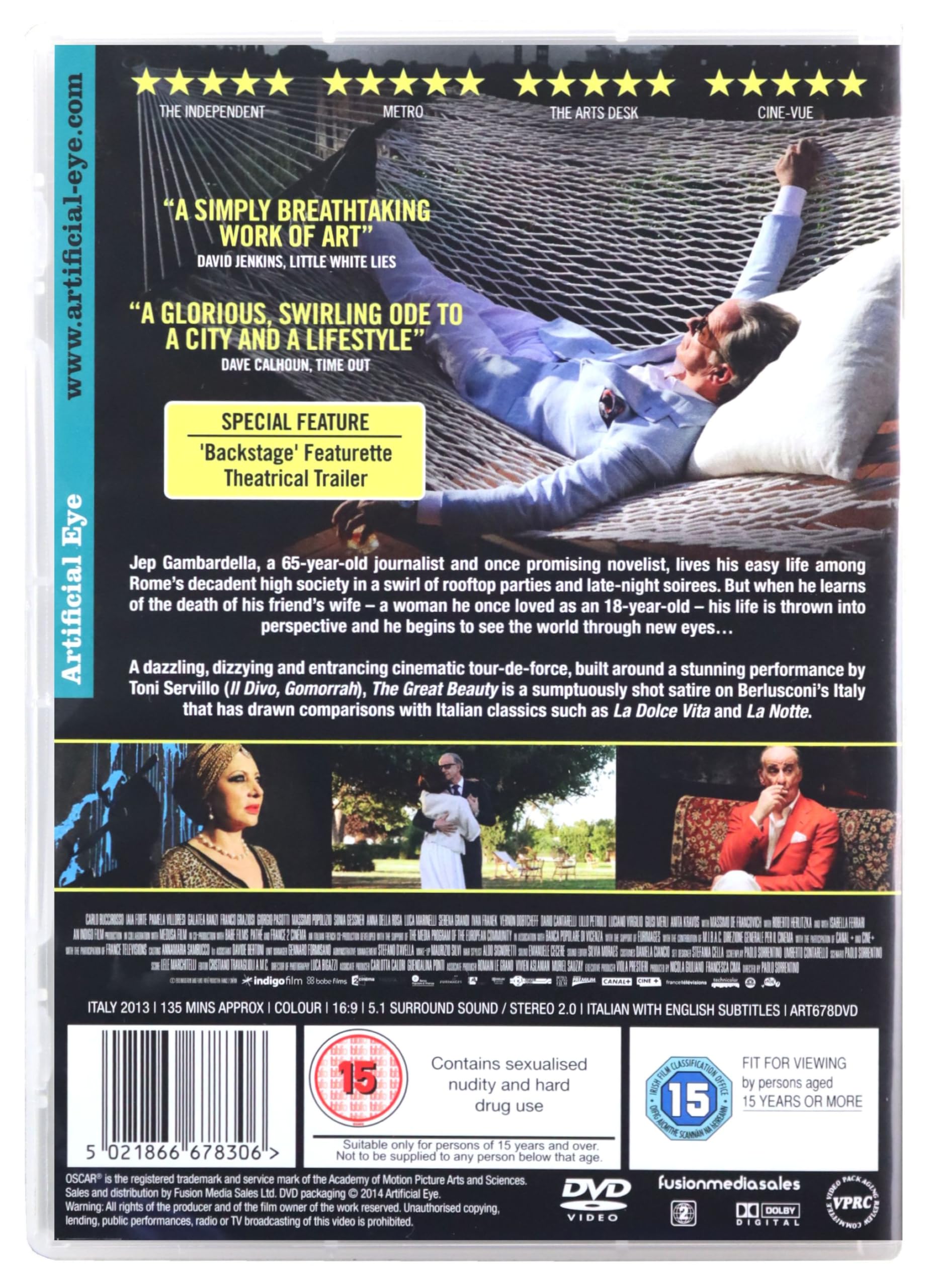

![The Great Beauty [DVD] [2013]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81nK-RhccPL.jpg)

Jep Gambardella, a 65-year-old journalist and once promising novelist, spends his easy life among Rome s high society in a swirl of rooftop parties and late-night soirees. But when he learns of the death of his friend s wife a woman he loved as an 18-year-old his life is thrown into perspective and he begins to see the world through new eyes. A dazzling, dizzying, mesmerising and hypnotic cinematic tour-de-force that has drawn comparisons with Italian greats such as La Dolce Vita and La Notte.A triumphant return to form for world-renowned visionary director Paulo Sorrentino (Il Divo, This Must Be The Place). Starring the multi award-winning Toni Servillo (Il Divo, Gomorrah).

Trustpilot

2 days ago

2 weeks ago

1 month ago

1 month ago