Full description not available

E**K

Polk presents a paradoxical lesson in being "near-great" yet forgotten and obscure...

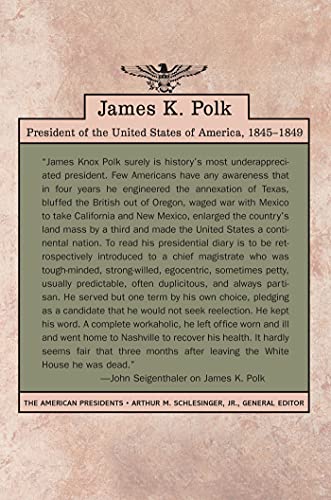

A single anomaly sticks out within that vast void of nineteenth century "undistinguished presidents" between Andrew Jackson and Abraham Lincoln. Huddled within names considered by many historians as the nation's worst ever presidents, such as the rebel John Tyler, Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan, James Polk seems almost miraculous by comparison. Though he has largely faded from public and national memory, the forgotten eleventh president frequently polls among the "near-great" to "great" presidents. Harry Truman granted Polk high praise, claiming simply that "he said exactly what he was going to do and he did it." So why the enduring obscurity? Polk's own extant writings apparently don't help his standing. In them, many commentators find a zealous and intolerant partisan, a braggart who often dismissed the contributions of his own cabinet and an overall joyless, humorless and arrogant man. Add to that his complete inaction on the subject of slavery, despite claiming it "evil" while simultaneously considering blacks as fully rational and human. This last admission puts him in quite a hideously nefarious category, as it suggests that he decided to ignore the fully rational and human suffering of slaves, presumably including the ones that he himself "owned" throughout his lifetime. Not only that, he didn't appear to consider beating slaves as abuse and thought that whipping slaves "had a beneficial effect." Of course these ideas also reflect those of his own time, but too many vile personality traits can easily whisk one into the dustbin of history. Yet Polk's astonishing political accomplishments, though also mired in controversy, keep pulling this apparently unlikeable and obscure president out of history's musty back drawers for repeated re-evaluations. Americans unschooled in their own history may find it surprising that the United States once went to war with Mexico. Polk did it. This war also added much of the Southwest, including California, all once Mexican territory, to the United States. People may also not know that the United States nearly went to war with Britain over the Oregon territory. It happened under Polk. In this case Polk manged to both avoid war and add the territory to the expanding nation. In fact, he arguably added more land to the United States than any other president besides Thomas Jefferson, and he did it in a single term. At the end of Polk's tenure, the still rather young country inhabited both coasts and roughly all of the land within its current continental borders. Many disputed the means that Polk used to reach his goals, but few disputed his actual achievements. The eleventh volume of "The American Presidents" series attempts a rehabilitation of Polk as a "near-great" president, while never arguing away or dismissing his often obvious and glaring flaws.Similar to other volumes in the series, this short book covers not only Polk's presidency, but also his early and later years. Born in 1795 to strict Jeffersonians, a squabble over a church ritual kept him unbaptized until his deathbed. Never devoutly religious, he only attended church later in life at the insistence of his future wife, Sarah. Polk's sickly childhood included a painful operation, obviously without anesthetic or sterilization, to remove urinary stones. Given the sensitive route that this surgery would have likely taken, it probably rendered him impotent, but at least it didn't kill him. Only the very lucky survived the horrendous, excruciating and unsanitary conditions of early nineteenth century surgery. Following his father's success in business, Polk attended the University of North Carolina in 1816, discovered law, served as a law clerk for the state senate and passed the bar in 1820. While practicing law, he took a case all the way to the Supreme Court in 1827, making him only one of seven presidents to do so. He won a state legislative seat in 1823, joined the National House of Representatives in 1825 and became a protegé of rising political star Andrew Jackson. Polk stood by Jackson through the 1824 "corrupt bargain" that put John Quincy Adams in the White House and defended "the will of the people" against "government by an elite minority." Polk sensed implicit Federalism, his bitter lifelong enemy, in the policies of Quincy Adams and Henry Clay. When Jackson won the presidency in 1828, Polk continued to support him through the Eaton scandal, though his own wife sided with the wives of Jackson's cabinet members in snubbing Eaton. Polk voted for Jackson's Force Bill during the Nullification Crisis, became Chair of the Ways and Means Committee and joined a corruption investigation against the Second Bank of the United States. He gave a well received speech on the subject that asked "whether we shall have the republic without the bank or the bank without the republic." His name recognition increasing, he became House Speaker in 1835 and began to incite the hatred of the new Whig party. The disastrous Panic of 1837 changed everything, including Congress, which turned towards the Whigs, and Polk returned to Tennessee and won the governorship in 1839. Following his first term, he ended up losing to "Lean Jimmy" Jones twice in a row, likely due to his affiliation with the then highly unpopular president Martin Van Buren. Polk's prospects looked rather bleak as the 1844 election approached, but hope often lies dormant in the unexpected.By 1844, public opinion overwhelmingly favored bringing Texas into the union. The battles of the Alamo and the Goliad still resonated, but the territory also poked at the looming giant of slavery. With the United States then split between 13 slave states and 13 free states, Texas statehood could break the precarious tie, tip the scales and obliterate the compromises that then steadied the delicate balance of power. Not wanting to drag the bugbear of slavery into the upcoming election, candidates Van Buren and Clay may have agreed to simultaneously declare that they did not favor Texas statehood. Two newspaper articles in different publications appeared on the same day and openly declared each candidate's opposition to Texas. It did neither any good, but it completely ruined Van Buren's chances of the Democratic nomination. Little did Polk know, this blunder, by an experienced politician that probably should have known better, almost single-handedly elevated him to the presidency. Back room dealings at the Democratic National Convention in Baltimore removed Van Buren from the ticket and unanimously nominated Polk after the eighth roll call. The first so-called "dark horse" candidate emerged from the shadows. Polk campaigned as "Young Hickory" and the Whigs found him annoyingly unassailable. He went to church. He didn't drink. He didn't fight or duel. They could have accused him only of being boring. Polk defeated Clay, who ran an arrogant campaign, by a razor slim margin of 38,000 votes. Lame duck president Tyler, possibly yearning for glory on his final day as president, signed the Texas annexation bill, but Polk signed the ratified agreement in late 1845, which officially made Texas the 28th state.Once in office, Polk instantly became an incessant workaholic. He apparently "incarcerated himself in the White House." His four "great measures," all of which he completed in four years, guided his administration. First, he lowered the 1828 "tariff of abominations" when his Vice President George Dallas broke a 27 to 27 tie in the Senate. Second, he re-created Van Buren's independent treasury, which turned out easier than anticipated. Astoundingly, Polk's Treasury lasted until the current Federal Reserve took it over in 1913. Third, he acquired Oregon from the British, which he accomplished without bloodshed. Lastly, he acquired California from Mexico. He had to lead the nation into war to fulfill his last measure, which he did in 1846, but not everyone rallied behind him. Whigs, including Quincy Adams and a young Abraham Lincoln, led the anti-war cry and many condemned the war as an imperialist land grab against an almost helpless opponent. Polk vehemently distrusted his Whig generals, Winfield Scott and Zachary Taylor, but they performed beyond expectations and he could find no replacements with his own party affiliations. Taylor's most celebrated military triumph, the battle of Buena Vista, occurred because he openly disobeyed Polk's orders. The war also began under questionable circumstances and some thought that the US, seeking the moral high ground, had lured and manipulated Mexico into attacking first. Scott, with his apparently large ego, took Mexico City and General Stephen Kearney went west to capture California. Mexico ceded California, New Mexico and land north of the Rio Grande. The US paid Mexico $15 million and the now mostly forgotten war ended in early 1848. The war didn't bolster Polk's reputation, but he had vowed not to run for a second term anyway, so he left office unscathed politically. He would have one of the shortest post presidential lives ever, dying only three months after leaving the White House. Some say that he had basically worked himself to death. Others went further and said that he gave his life to his county. Zachary Taylor, despised by Polk, but now a national hero, succeeded him to the presidency. Polk gradually faded into history, highly accomplished yet also fairly unpopular. A curious mix."The American Presidents" series volume on Polk paints a picture of a man with conflicting, and often undesirable, character traits who nonetheless reached the presidency and miraculously achieved some very ambitious goals. The book does a good job of portraying the tense dichotomy between his political successes and his less than ideal personality. It also helps explain his bizarre and obscure place in American history. The book mostly glosses over the circumstances of his death and his legacy and it doesn't even mention the probably very uncomfortable transfer of power to Taylor. But it does clearly demonstrate why Polk shines out among his immediate presidential predecessors and successors. He seems destined to remain neglected and under-appreciated, perhaps a paradoxical victim of his own "near-great" presidency.

R**O

Goal-minded but no leader

A college professor I know says James K. Polk (1845-1849) was our greatest president. Why? Because Polk did exactly what he said he would do. He said he would serve one term and achieve four goals: lower the tariff, re-create Van Buren’s independent treasury, acquire Oregon from the British, and acquire California from Mexico. And that is exactly what he did. Mind you, the first two goals were within his reach, but the latter two? Not so much. In fact, at one point he risked putting the United States in the untenable position of having to fight a war on two fronts—in the American Southwest with Mexico, and in the American Northwest with Britain. James K. Polk was a risk-taker on a grand scale, foolishly so perhaps, but he got away with it. Still, the stress must have been terrible. He left office in an exhausted state and died three months later. John Seigenthaler’s short book (156 pages) makes for an engaging read and is a nice introduction to our nation’s 11th president.James K. Polk would have been right at home among today’s faceless corporate managers who do not lead by building consensus, but rather operate behind closed doors consumed with endless analysis. People—the ones on the front line—do not figure into the equation. Like President Jimmy Carter, Polk was a micromanager, but without Carter’s deep-seated humanity and folksy grin. The author describes Polk as stiff and humorless, a guy who never took a vacation, “an obsessed workaholic, a perfectionist, a micromanager, whose commitment to what he saw as his responsibility led him to virtually incarcerate himself in the White House for the full tenure of his presidency.” Polk was also a thorough Jacksonian Democrat committed to slavery and to small government; the enemy of paper money, the national bank and bankers in general; and a fierce foe of Henry Clay’s American System of national improvements. Nonetheless, Polk was a shrewd politician who read the mood of the nation perfectly, who campaigned for lowering the tariff and annexing Texas. Against overwhelming odds, he received his party’s nomination and was duly elected president.In office but a year and a half, Polk achieved three of his four goals. Having successfully bluffed Britain with the threat war in the Northwest, on June 15, 1846, he had reached agreement with the British on acquiring the Oregon territory; six weeks later he signed the tariff bill into law; in August the legislature passed his Constitutional Treasury. Texas, meanwhile, entered the Union, on Polk’s watch, of course, December 29, 1945. That left California—and a prolonged war with Mexico to get it.As the war went on Polk became increasingly frustrated with his two ranking field commanders, Major General Winfield Scott and Brigadier General Zachary Taylor. With much smaller forces than the Mexican army, but better led, Scott and Taylor won battle after battle. But victory was not the issue; with Polk it was their political affiliation: Scott and Taylor were both Whigs—and both had political aspirations. “Nowhere does Polk’s intense partisanship appear more obvious or more wrongheaded than in his diary comments about Taylor and Scott,” writes the author. “His extensive musings about their Whig leanings reflected a vindictiveness that sometimes was petty and bordered on irrational.” Meanwhile, with criticism mounting against the war, the Democrats lost the House of Representatives in the midterm elections. A young Congressman named Abraham Lincoln was against the war, as well as the political leader he greatly admired, Henry Clay, and former president and now Congressman John Quincy Adams. They believed the war—which the U.S. had provoked— was being fought solely for expansionist aims and was ethically indefensible. Surprisingly quiet on the matter was South Carolinian John Calhoun who had bedeviled Andrew Jackson’s presidency with the Nullification Act and the threat of Southern secession. Why so quiet? Because he had his eyes set on expanding slavery into Texas and into the potential for more new territory—California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona and New Mexico.After reading this book, I couldn’t help thinking of William Shakespeare’s play (Henry IV Part 2) where the dying king tells his son, “Be it thy course to busy giddy minds with foreign quarrels.” The Mexican-American War was that, a foreign conflict that busied the minds of Calhoun and the slave-holding South with dreams of a thousand square miles of new land to plant more cotton tended by slaves. It was during Polk’s presidency that the term “Manifest Destiny” entered the American lexicon, thanks to newspaper editor John Sullivan who coined the term in 1845--as a justification for war with Mexico.Polk had succeeded in achieving his four goals, but at what cost? Almost 13,000 American soldiers died, and Polk himself died soon thereafter. Having lost nearly half of its nation, Mexico was crushed both economically and psychically; and slavery, the greatest single issue dividing Americans, was encouraged to grow with expansion into Texas and the new southern territory, thus hastening the onslaught of the American Civil War. Does such a legacy make Polk our greatest president?

Trustpilot

3 days ago

2 months ago